Yes, Hanya Yanagihara is among the most brilliant novelists of our time, but we’ll get to that later. For now, let’s discuss how this mag-world veteran is creating a brave, new T as its editor-in-chief!

What coaxed our favorite contemporary novelist to return to magazine publishing?

I’ve been a magazine editor for almost 20 years, and the book writing has been a side hustle in certain ways. You don’t spend 20 years clawing your way up the masthead to turn down the one job you want. I was lucky to be able to take a gap year in 2015, but this [opportunity] was really the only thing that brought me back to magazines. Many of us here at the magazine feel terrifically fortunate. It’s one of the few books—and maybe it’s the only book—left in town where you have the resources, the autonomy, the independence, the authority, and the imprimatur of the company behind it, and you get to do what you want. And you don’t have to worry about newsstand [sales]. That privilege is so, so rare. It’s really the only title I wanted to ever do.

When you got the job, you posted that you’d be working with “the smartest, chicest, strangest staff in town.” Why so strange?

You’re not going to make a Condé salary here, and you’re going to abide by Times standards and ethics. The editors here aren’t here for the swag or the perks—they’re here because they get to do unusual work on their own terms. There’s a lot of porousness between departments here, unlike almost any other luxury magazine I’ve ever worked at. One of the things that makes me uniquely lucky is that I’ve worked with almost everyone here before, and these are the people I would have hired had I started my own magazine or had I had to re-staff. The amount of help and grace and trust that they’ve given me has saved me. I came in, and I told David Farber, our men’s style editor, and Malina Gilchrist, our women’s style director, “I really don’t know anything. You’re going to have to really teach me.” And they have, with such patience and faith. I was able to rely on them for everything, and not just them—Nadia Vellam, our photo director, and especially, Minju Pak, our managing editor, have been so helpful. At every step of the way, big and small, they’ve helped and bolstered and prevented me from making my own mistakes. It’s really because of them that this magazine is still coming out!

What are the qualities that make someone an inherently interesting subject for T?

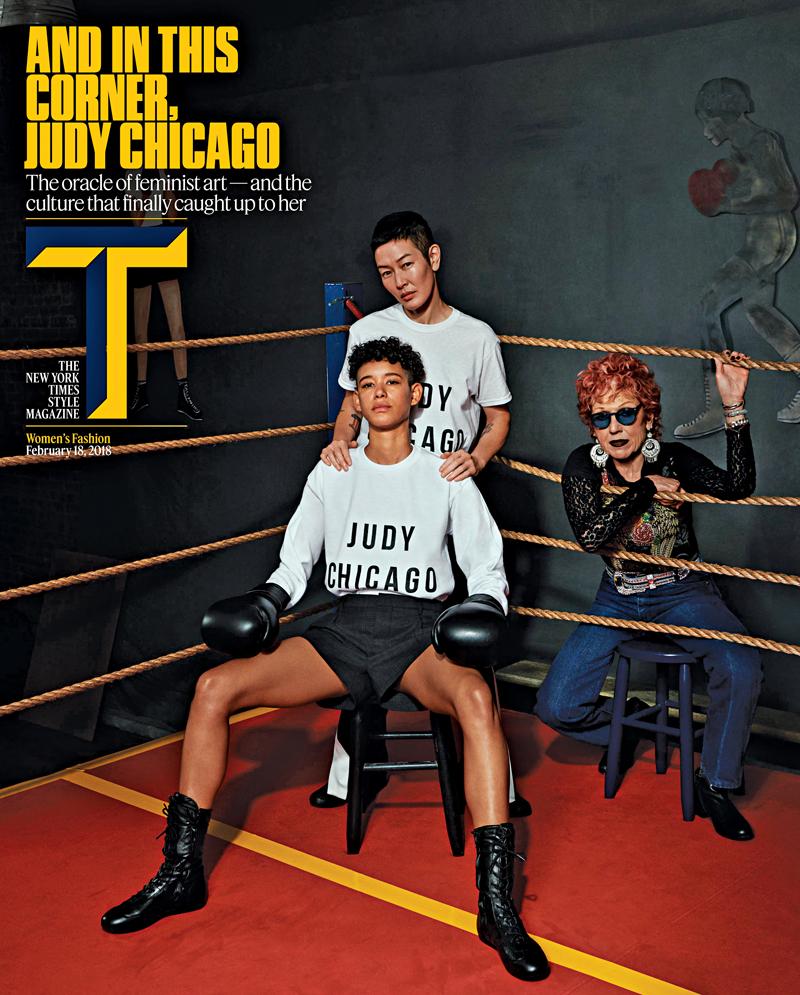

The only people we cover are people we admire—someone who has, in some fundamental way, changed the field or the culture. I don’t want to spend real estate making fun of someone or disparaging them. It’s precious space, and we don’t really have room for that. Plenty of other people do it, and they do it very entertainingly. It’s also about recording what feels urgent in the culture—recording hidden moments you don’t hear about. What this magazine has always been good at, from Stefano [Tonchi]’s days all the way up through Deborah [Needleman]’s days, has been taking a moment, explaining why it’s relevant, and how it happened.

The #MeToo movement has been such a watershed moment in American culture. How has that influenced the conversations you’ve been having at T?

I’d worked for Deborah, and I loved Deborah’s book, but it was very much a book for the Obama years, by which I mean that it didn’t have to engage directly with the culture in the way that you have to now. It did, sometimes, but now, if you pretend that fashion or design or literature or art is divorced from politics or contemporary society—and it never has been—you look terrifically provincial. Every form of art is grappling with what it means to live in this current political reality. If the magazine doesn’t do that as well, then it does become a meaningless enterprise, a magazine full of pretty things, and that’s never what this book has been about. We stay in our lane; no one here is Peter Baker or Michael Schmidt, we’re not going to be able to comment on the White House’s goings-on or on legislation—but we can talk about how the culture is responding to it, even if it’s in oblique ways. But the book still has to be beautiful, it still has to feel luxurious, it still has to “feel expensive,” as our creative director always says.

A year into the Trump administration, do you feel like we’ve become more provincial?

American culture is naturally provincial, because it’s so inward. You kind of cannot help it, in this particular moment, to look inward and to be interior. One of the things that living in New York does is to make you feel that the world is coming to you. You begin to think that you don’t have to leave. More and more, in this political moment, Americans should be traveling, in whatever way they can afford, and I know that that’s not a reality for everyone. But for those of us for whom it is a reality, it’s essential. You see, immediately, how much America affects the rest of the world—how much they’re responding to us. That’s something that this book can also do. One of the things I talked about when I was applying for this job is that I want the book to feel more truly international. It’s always done great coverage of Italy and France, because that is where a disproportionate amount of design and fashion continues to come from, which is remarkable and a story in and of itself. But there are also stylish and interesting and artistic lives being lived in Japan, in Iran, in Brazil, in Northern Europe, in Eastern Africa.…

Where did you travel during your gap year?

A lot of it was repeat—Morocco, Spain, Germany, Sweden, Finland, Bali, Sumbawa, Cambodia, Burma…I’d only been to Northern Africa before, so I went to Tanzania, and to Australia and New Zealand. I think I spent two weeks in New York, in total. There is nothing more useful for an editor or anyone interested in writing or seeing or editing than being in a constant state of discomfort or vulnerability, which you are, naturally, when you travel, even if you travel in a cosseted way.

Presumably you’re traveling less frequently?

I’m traveling a lot more to Europe. I hadn’t been to France or Italy in years, and it’s been lovely to get to be back, but it means I get to go to Asia a lot less, unfortunately.

What are your thoughts on Fashion Week?

I did all of New York, Milan, and Paris. The splendor of it, and the excess of it, and the seriousness of it—I mean, I loved it. It was an extraordinary experience. I also discovered that my stamina is poor. I came back and I was sick for maybe a month. The fashion department seemed perfectly fine, but I was really dragging by the end, but I loved it, and people were nice to my face, which is frankly all I care about.

Any highlights?

I got to meet Rei Kawakubo, and I was told that she smiled. I didn’t really see that, but I was told she was very happy, which was an honor. Especially in the age of Instagram, you forget how great it is to see these shows live. It’s like a play that opens for one night on Broadway, then closes. It’s that sensation, again and again and again. The thought and the showmanship that goes into not just the clothes, but the presentation itself…you can’t help but feel honored to be there. I know this sounds romantic, but I thought, the second I start feeling jaded about this is the second I know I’ve been doing it too long. Of course, the other fun part is complaining, and grousing, and commiserating, but that’s also a part of the theater of it.

For The Greats issue, you chose to write about Dries van Noten. Why?

My mother is a great seamstress—when we lived in New York when I was a child, she had a children’s line that she sold at Bloomingdale’s. She has always loved Dries van Noten, and she loved his colors, she loved his patterns, she loved his references, the drape of his clothes. I came of age knowing of him, and very few other people. One of the things I was able to slowly articulate is he’s one of the few designers who have such a holistic vision, from the way he lives to the way his stores look, to the way his clothes are, to the way his garden is…you can look at any aspect of his life and it makes sense within the larger universe of what he creates. As someone who is trying to make a holistic creative vision, I deeply admire someone who can and has made such a universe that makes complete logical sense and is completely his. It’s one of the things that I appreciate even more, in fact, after publishing [my novel] A Little Life, because you understand that as an artist—roughly, reductively—you can either have riches or freedom. He’s one of the few people who has made a successful business while never having to concede. As someone who really values my independence on the page and values my right to make the decisions that I want to make, creatively, I deeply admire someone who is able to ride out the hard parts of owning a business through sheer belief in the consistency of his vision. And I love the clothes.

T is so serious, but it’s also infused with a sense of humor. You’ve had cats, you’ve had Bread Face…what do you find funny?

I don’t think the magazine is funny. I don’t think that’s a problem, being serious. Having said that, I want us to be serious and admiring but at the same time, irreverent. The digital side is a furtherance of the conversation that happens in the book, but it tends to be a little more loose-limbed.

Could you ever see T as a digital-only property?

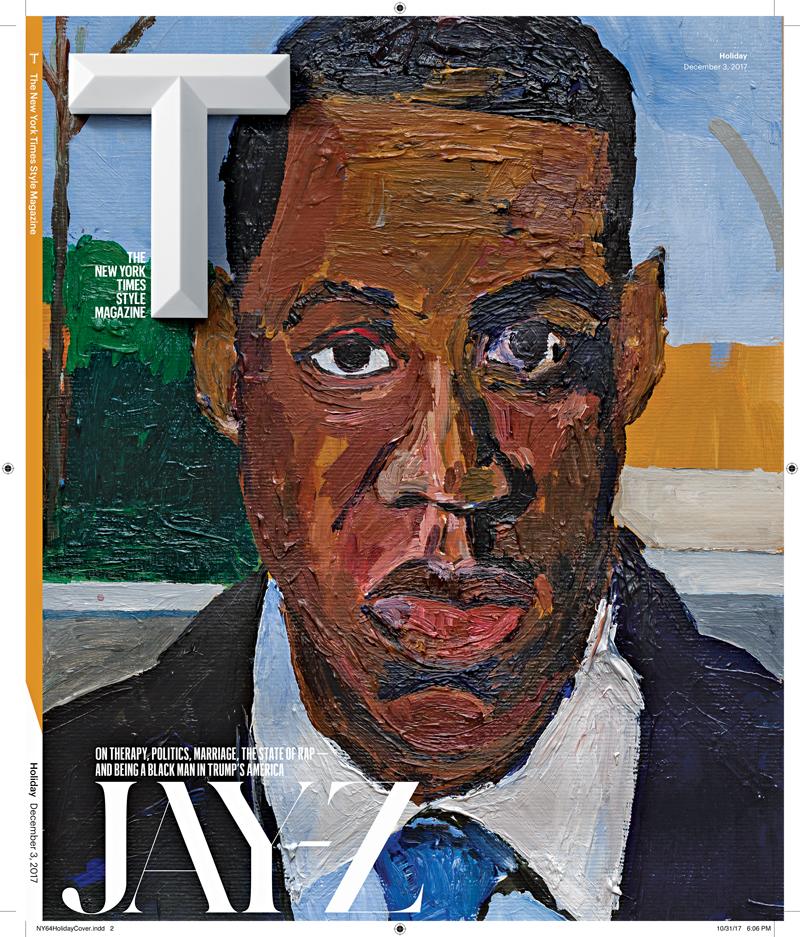

Any magazine could, in theory, be a digital-only property. One of the things that I talk to Isabel Wilkinson, our digital director, and our staff in general about is that something really has to earn its place in the particular media it lives in. What I don’t want to do online, for example, is a 350-word write-up on a store opening. The same goes for the book—we have to think of a way to illustrate a story that could only be illustrated in print, with the luxury of big space and air around the photo. Every single magazine editor says this, but [print] has to feel like an experience. On the other hand, we do want to start conceiving more stories that are holistically planned. The Jay-Z story was an extraordinary but good example of that. We knew from the start that we were going to have the interview in-book, that it was going to live online, that there was going to be a full-length video and Instagram teasers—so no matter what channel you came to the story from, you’d have a slightly different experience that together, when you looked at the puzzle, would form a whole. But you wouldn’t need to necessarily do that—you could encounter it purely as a 35-minute documentary, and that would be satisfying. I hope what you’ll see is a greater conversation among the platforms, with the magazine leading, always.

In your editor’s letter in a recent issue of The Greats, you wrote that planning for the 2018 edition would start in January. True?

The meeting is on Friday at 3 p.m.! [Laughs] Everyone’s been invited, and they’re told that they must bring a list.

Are you writing another novel at night?

No. At night, I’m working on the treatment for the screenplay of the series of A Little Life. Who knows what will happen—it could never sell. I always say that in book publishing, people are constantly telling you, “This is never going to work. This is going to be a disaster.” And they’re usually right. And then in Hollywood, they’re saying, “This is definitely going to work. This is going to be great.” And often it just never happens. So who knows?

Have you encountered some superfans of your fiction amongst the fashion crowd?

Yes, and it’s been really sweet. It’s always a compliment when people read your work. It’s particularly thrilling when you’re being told this and you’re wearing their dress.