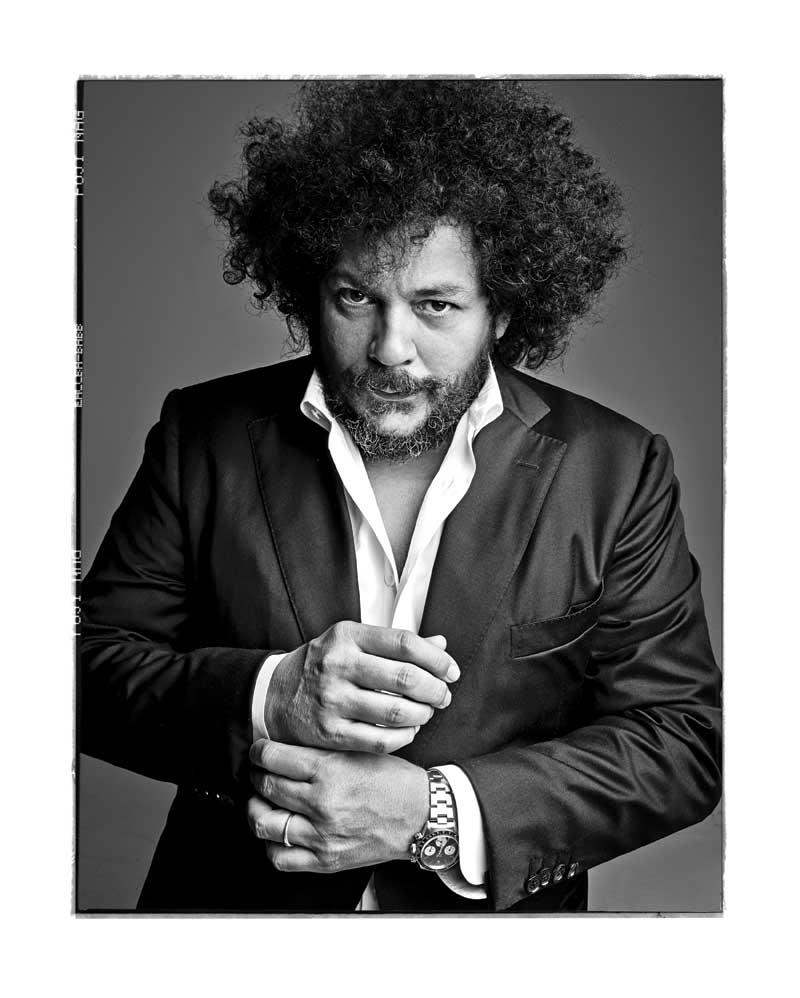

In an era of sensory overload, master creative director and retouching guru Pascal Dangin has that all-too-rare ability to make images stick. Over coffee at his soaring new office space in Chelsea, he explains his mastery of the medium.

What happened to your building in the Meatpacking District?

I sold it. I moved the backbone of the company—production, printing, film editing—over to Gowanus. I go there every other day, but more importantly, I have my team come here. This space is more of my own space—I can think without too many people around me.

What’s your staff setup? How do you divide your time?

We have about 60 employees total, between design, production, and post-production. I don’t really divide my time. It’s not divisible.

You founded your creative agency, KiDS, in 2013. Why was it the right time?

I don’t know if it was the right time, but it was what I wanted to do. It felt like a natural evolution of my work after all these years. I had sort of done it for a long time—behind the scenes, I suppose. I didn’t really make a plan.

Who were your first supporters at KiDS?

Alex [Wang] really believed in what I was doing, and I felt I could relate to him very well with the urban quality he had, and the groundbreaking, no-recipe instinct. I liked him a lot, and he was instrumental in making me believe that there was something there to do, creatively.

Whose idea was it to shoot Anna Ewers basically naked, except for a pair of jeans, in the Wang ad campaign?

It’s usually a collaborative effort. I’ve always loved a picture from the viewpoint of the legs, and I felt like it was okay to pull the jeans down to her ankles. She was amazing—she played the game with us. But it’s about creating an arresting image that stops people in their tracks, just so you get a chance to impress an image on their mind. Perhaps they want to see it again. We are bombarded with billions of images all the time; it’s perhaps difficult to create an image that people actually respond to—positively or negatively.

What do you think about the quality of the images we’re seeing all day? Are they by and large good? By and large bad?

I would say by and large good. One of the reasons I started KiDS is because I wanted to really gain control over the image process I felt was slipping away. There were generic ideas about how to approach an image. I felt that by controlling it A to Z, from its conception to its realization, that I would try to bring some quality to the photograph, as opposed to a generic image.

Do you worry about distribution of images?

No, not at all. I think the digital medium is amazing at sharing and displaying the work. It’s perhaps not as tangible as the page of a printed magazine. I think magazines have a huge role to play. They aren’t so much about the news anymore, because of bloggers and Twitter and Instagram, but women are still looking to magazines for an opinion.

How do magazines need to evolve in this new world?

I want to see magazines with more of an opinion—less of giving what people want, and more of what they don’t know what they want. They should shift their desire from being newsworthy to evolve more as the trendsetters they once were. People will find inspiration through Instagram and Pinterest and the opinion of their peers, but there is a leadership that magazines have, a taste.

Are magazines still a dynamic place to place ads?

Very much so. A magazine that stays on a table, or in your life, for however long, plays a different role than an image that is just wiped away from your device.

What about video?

Video is huge. It’s really important to communicate a style, a mood. Obviously, sound and images together create a better story. There’s a misconception about how to prep a [fashion] film—I feel like a lot of the films are ending up like glorified PDFs, made of stills. A series of images as a flip book isn’t really a video; it’s more of a screen saver. It’s just that video requires a lot more writing and a different type of team. It’s probably still too cost-prohibitive. Fashion brands don’t want or need to go to TV, and it’s a web-only thing, but the ROI is so difficult to calculate for those brands that it’s hard to justify a half-a-million-dollar production that will stay for a few minutes. Eventually, as budgets shift and evolve, we’ll see more and more of them.

What do you make of the movement of choosing more anonymous, behind-the-scenes designers to lead European fashion houses?

At some point, the John Gallianos and Lee McQueens and Tom Fords were anonymous. I don’t see a difference between now and then. It’s just a matter of finding the right fit: Do I have the right creative mind to lead this brand? Does this person understand where we want to be?

Why did you name the agency KiDS?

It stands for “knowledge in design strategy.” But children, to me, are very new. I have kids, and they tend to have the most amazing way of coming up with new things, almost from an instinctual point of view. They tend to tell the truth and be fearless. They’ll go to touch a flame, not knowing that it’s going to burn them. I also didn’t want to name the agency with my name.

What do you look for when you’re hiring?

Collaborators—people I can have around a table, who can think and develop ideas. I look for a dedication to the pursuit of excellence, in terms of image. And I’m also looking to always have a challenge of the mind—to question why, or why not, we could do things.

When you got started, there was a different mentality among photographers—many didn’t want anyone to touch their photos. You changed the game.

Well, they always touched their pictures—this makes me feel very old—back in the day. They didn’t have control over their production as much as they would want. Digital post-production has given them that control. I, perhaps, was interfacing that a lot in the beginning, but the advent of technology—the awareness, the know-how, the software evolution—has given everybody the ability to control how the image is going to be seen and perceived. I think that’s the control they always wanted to have.

What does the photographer of the future look like?

I would say that a photographer is a photographer, with the exception of a fashion photographer. A fashion photographer is really a different type of photographer, because of the subject matter. There are two kinds of fashion photographers—people who love fashion, to a point of passion for it, who love clothes, who love girls, who love hair, love makeup and shoes and bags, and tell the story of a woman through everything around her. These people tend to be fascinated by the clothes themselves. And then there are other photographers who are more into portraits, but still love style. They have a very clean sense of how images should look, and how girls or boys should be. They may not care as much about fashion. The evolution will still be the same way. If a photographer on a set is ultimately the person responsible for conveying an image, his choice of light is not enough—he’s going to have to oversee how hair and makeup are done, and obviously stylists are there to fill that role as well, but the collaboration is huge between them. Some photographers don’t understand the basic fundamentals of what fashion is, and maybe they should do other types of photography if they don’t really have a keen interest for style.

What do you make of all the masses online who are protesting these retouched photos?

[Unretouched photos] would be a lot cheaper, and they would take less time. There’s such a misconception about what’s retouched and what’s not. A photograph is one point of view in space. The way the camera looks at that particular subject is very different from how that same camera would look two inches on the left or two inches on the right. Take a very simple image, like black and white. Black and white is not real. I can change that photograph by printing it, without even retouching it, and I can make you feel anxious or sad or happy. Of course, there have been people who have perhaps gone too far, but I say, retouching is the same thing as putting on red lips. When you do that, you are drawing the viewer to a point in your face that you would like them to see first. It’s always a journey—what is the first thing you see, what is the second thing, the third thing, and so on. It’s like a map. To be attractive, or to push, we all naturally do things to our bodies and image to attract attention. Why do we put highlights in our hair? Why do we pluck our eyebrows? Why do we put on a push-up bra? Why do we wear a corset? Why are we doing all of that? We’re retouching ourselves, in some ways. We’re manipulating our own reality. But most importantly, it makes us feel better.

How has Instagram changed our relationship with photography?

I don’t think it changed it—I think it amplified it. Our parents had boxes and boxes of pictures, and now, we just have a digital version of them, in an aggregated community. It’s a great opportunity for people to show what they have. But again, the sea of sameness is quite vast.

On the subject of Instagram stars, how did you hook up with Olivier [Rousteing] on Balmain?

He liked what I was doing on Balenciaga, and he wanted to meet me, and we met. We just shot the children’s lookbook in Paris. It was great—the kids are amazing; they give you a whole different set. There’s a lot of direction: Do that, don’t do that, be yourself, don’t be yourself.

Easier than celebrities, or more difficult?

I don’t think that any of it is difficult. It’s just a matter of adaptation to your subject.

You shot Kim Kardashian and Kanye West for Balmain. What do you think about their power as imagemakers?

Kim definitely has created a brand for herself out of absolutely nothing. She was able to impose her image and share her image in ways that haven’t really been matched until now, and kudos to her for being the Kim Kardashian that she became. The image of the kiss [between Kardashian and West] was very important to me. The campaign was all about love, and I tried to show one intimate moment.

Alex’s last collection for Balenciaga was so beautiful and romantic. What was going through your mind during the show?

Alex did the collection that he really wanted to do. Perhaps at the beginning, when you go to a brand like Balenciaga, you have to be influenced by what had been. [For the last collection], he kind of said it, and I only wish perhaps he had done that earlier. But he didn’t, and so be it. I think he was so happy to be part of that—he learned so much, at least that’s what he said—and it’s been a great adventure for him.

You have so many different collaborators, and you have so many people on your staff now. Are there any photographers you still work with on a one-on-one basis?

I work with all of them on a one-on-one basis, to a certain extent. Two people secluding themselves and having discussions is sometimes a better way to exploit the potential of an idea. I usually edit, the photographer does his own edit, and we merge the two. Then we fight—no, we don’t fight, we don’t fight. [Laughs] Another pair of eyes is good.

What was it like to be profiled by The New Yorker?

It was great. I was happy and proud. I think my mom was prouder than I was. And my children…

Was it limiting to your creativity to be followed around by a reporter for months?

No, [writer Lauren Collins] was amazing, and very patient. I brought her to my world, and it’s tedious. Long hours. And she was very keen on understanding. But that’s the thing—The New Yorker touched on really the retouching aspect of the work. People who know me very well thought that it wasn’t as complete as it could be. Other people who didn’t know me were very interested in it. For some reason, people think that retouching has been everything, but it’s always been one sliver of my work.

How many full-length feature films have you done?

Seven or eight. With Gus Van Sant, James Gray, Woody Allen…I did the last two films with him, Irrational Man and Magic in the Moonlight. He’s amazing to be around. That’s what I love about my work—I get to be with people like that. You can observe how they work very closely.

What’s your favorite Woody Allen movie?

I love them all, but I think it’s Annie Hall. I do like a good sense of humor, as long as it’s intelligent and dry. A good laugh is a good laugh.