As the longtime steward of Esquire, David Granger was a best-in-class kind of editor, delivering a mix of heart-wrenching and guffaw-inducing stories on the monthly. When he exited the title this spring, more than a few were heartbroken, but over late-afternoon drinks at Old Town, he reveals what’s next.

What’s happening?

When I got s**t-canned from Hearst Corporation, there was a little period of panic: What was I going to do all day? For the first two or three weeks, I took way too many meetings, because I thought I had to fill up my days. But coming into the city and going to meetings was just a drag. I decided halfway through that period that starting June 1, I was going to do nothing for as long as I could. No plans but lay by the pool, play golf, play tennis, have a beer at 10 in the morning, read all day, nap in between reading and drinking beer. It was fantastic. It became clear to me pretty early on that I’d been asking myself the wrong question, which was, “What am I going to do?” The question I should have been asking myself is, “What do you want to do?” I also figured out that I don’t want to work for anybody. I got my financial adviser and my lawyer to help me create a corporation: I’m an officially sanctioned New York state entity called Granger Studios, and I have taken on a few clients. I’m currently actively advising a tech start-up, a magazine start-up, a national magazine, and a mobile publishing platform. The magazine start-up—Racket—is my first pro bono client. It’s a quarterly about tennis with high production values. The other half of Granger Studios, which may end up being the bigger half, is that I’ve affiliated myself with two different literary agencies: Kuhn Projects, run by David Kuhn, and Zachary Shuster Harmsworth. Ultimately, I want to facilitate the creation of things that have a chance to last. I want to get outside the endlessly shrinking news cycle. I’m just getting started with those two things, and I have a list of 20 projects that I’d like to get done—some are books, some are TV-related, some film-related. One, if it ever happened, could be a musical.

I wouldn’t have pegged you for a musical lover.

I’ve seen two that I’ve liked in the past two years, Hamilton and An American in Paris. I’m always so uncomfortable in the seats because they are tiny, and I have a little claustrophobia thing. In both cases, I forgot how uncomfortable I was. Those are pretty much the only musicals I enjoy, unless you count The Lion King, which literally changed my life. It made me want to make a better magazine and be a better human.

Any interest in writing a book?

My friends and my agent were up my butt for decades to write a book. I never found an idea that I was convinced I would actually do. I’m also aware how difficult writing is—I got to hire so many people who are better than I could ever be, so it’s a little daunting to think about doing that for a living. But it’s not out of the question.

What kind of story turns you on the most?

There’s one story that has constantly delighted me, from idea to final publication. I got an idea memo from Peter Griffin, my former deputy editor and the smartest man in the world. The entire idea was one short interrogatory sentence: $1,000 for your dog? We went to Tom Chiarella, who went on the road and he started to try to buy things from people for $1,000. He’d go into a bar and say, “Would you sell me your wallet for $1,000?” He then moved to going into Walmart or Kmart and asked people to sell their wedding bands for $1,000—in front of their wives. The final thing was he had to ask somebody if they would sell him their dog for $1,000. The first couple of people he asked were so angry at the thought of it that he was physically threatened. He was about to give up when he saw an older woman in downtown Indianapolis walking her dog. He went over to her and asked her, and she said, “Can you give me a minute to think about it?” She then said, “I think I know what you’re doing—I think you’re trying to figure out what people value. I would never consider your question, but I’ve been diagnosed with cancer, and I know I’m not going to live much longer. So I’ve been wondering what I would do with my dog.” It went from being this frivolous little gimmick story to something really serious about what people value; it was beautiful from beginning to end. When a story takes the readers and me on a journey like that, it’s kind of amazing.

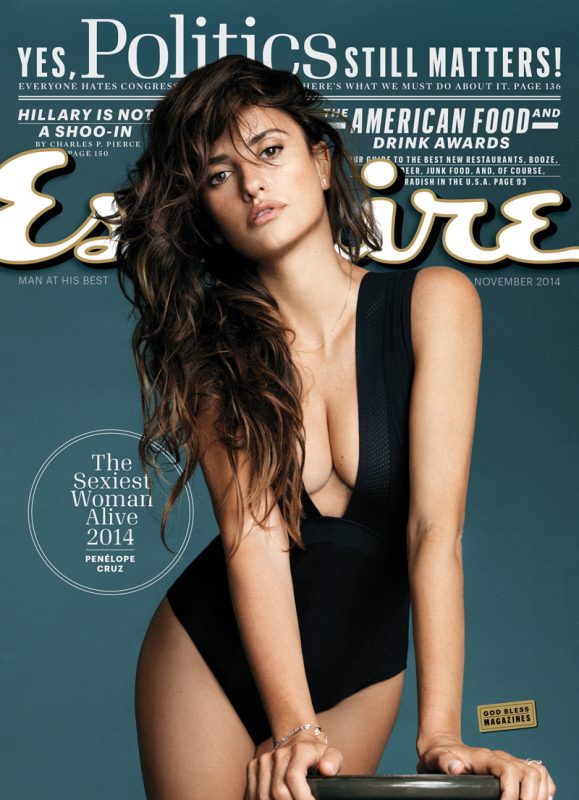

- This image released by Esquire shows actress Penelope Cruz on the November 2014 cover of “Esquire” magazine. The magazine has named Cruz The Sexiest Woman Alive for 2014. (AP Photo/Esquire)

Are you a visual guy?

I don’t know about that, but the most fun we ever had putting out issues of Esquire was in the design and packaging process—coming up with new visual languages to express what you’re doing. A lot of that was f**king around with type or f**king up photography, making pages seem more visually interesting by writing on them or doing lots of weird things on the margins. In a limited way, I think I’m visual because I always want the pages in a magazine to be physically exciting. Do I just put pictures on a page and think that’s art? I’ve never been that guy; I’d rather have fun. My priority is always entertainment. A lot of magazines you might think are visually driven to me seem static—I always wanted our pages to be really active. There are some things that existed simply to make people laugh, or simply to thrill or inform them. Then there are other things that existed because we wanted to evoke an emotional response. You treat all those differently in terms of writing style, design, photography, or illustration. A lot of stories that I published were meant to be taken extremely seriously—some were sad, horrifying—but sometimes they were funny, sometimes they were both. Any entertainment medium’s main competition is every other entertainment medium. People aren’t going to choose your outlet if it’s boring. I always live in deathly fear of being boring. So I maybe overcompensated and make it a little more frantic than it actually needed to be.

When did you start really feeling the industry’s change of focus from print to digital?

Right around the time that we were trying hard to do gimmicks for our 2006 covers was when all the media started to say print was dead in all its forms. They were mostly talking about the newspaper industry, but also books, and they were lumping magazines in with it. I actually think at that point—2006, 2007, most of 2008—magazines were actually extremely healthy, and we had great years. Then the recession hit and everything went to s**t, but the media pundits were still going, “It’s because of the nature of print; it’s because traditional media sucks,” as opposed to [reporting] the world just ended and the nobody has advertised it. I don’t think we ever recovered from that dual blow. 2013 and 2015 were two of the best years in Esquire’s history ever. If you work incredibly hard and have the advertising support and have your expenses cut to the nub, you can actually make a really profitable magazine. The thing that has discouraged me in the last couple of years is the way that all the big magazine companies have been running away from print; they all want to be seen as agnostic content providers. I’ve always thought there was value in print, because it’s a fundamentally different experience if someone is reading a tweet, or watching videos, or reading a blog post than it is if they sit down and read “$1,000 for Your Dog?” There’s a different level of engagement—what all the magazine companies have done is equate those experiences. There’s a much more qualitative experience, for the most part, in reading a magazine, even if it’s not the deepest, most thoughtful magazine in the world, than there is in the vast majority of digital experiences that people have every day, because they’re so short. There’s also difference of intention, and what the creators are doing in creating a magazine story from creating a Facebook post. When the magazine companies decided they were going to play the digital game and say all content is the same, I think they demeaned the potential of magazines. That’s discouraging to me; I think magazines are a really special experience. One of the reason’s I’m working with Racket is because they believe in that. They are going to charge $100 a year for four issues. If they get advertising, that’s great. It’s like the Lucky Peach model—it gets a good amount of advertising; they also get their readers to pay a lot of money for every issue.

What do you think about the word content?

I f**king hate that word. If I ever use it, I always use the word editorial in front of it. It just means that whatever you fill your space with is of equal value. It drives me insane; I don’t believe that’s true. There are really valuable, thoughtful, ambitious attempts at journalism, and I think there are really s**tty attempts to entertain people for one millisecond. Those are really different experiences.

Did you suspect you were about to get fired?

Nah, because we had a really good year in 2015.

What was it like on your last day at Esquire?

There was a long time between when I knew I was fired and when it was announced and when I actually left, so it was the longest departure in the history of magazines. David [Carey] wanted me to stay because he was working on various transitions, and I said I’d be inclined to do so if I could get in a final issue. I had so many teary farewells in my office—people coming in to hug me and cry in front of me—I knew I couldn’t take too much more of that, because I was going to start crying all of the time. I gathered my senior people and we went to lunch, and then I just trap-doored, which is the way I leave everything. I have this policy against saying goodbye at a party. I’ll send a thank-you note later, but I’m not going to seek out the host and go, “I’m leaving your party now.” I told my assistant I was going to lunch and I just didn’t come back.

Who was the first person you had lunch with after you left Esquire?

When it got announced, people were really surprised. I got so many e-mails and texts. A lot of people wanted to take me out. Before anyone knew I was fired, I started going to talk to people who meant a lot to me. The first person I told other than my wife was a guy I didn’t know all that well, John Maeda, whom I consider a wise man; I thought he would have advice. He said, “How you leave will determine your legacy.” He was telling me to leave on as positive and gracious a note as I could. I thought that was really smart, and I tried to. So I threw a party for myself, you know?

You had somewhat of an emotional moment at the National Magazine Awards, when you got a standing ovation accepting Esquire’s award for Essays & Criticism.

Well, I didn’t cry or anything. I made a couple of jokes before I thanked my team. That was frickin’ amazing. I was trying to keep the news from coming out until after the National Magazine Awards, but then it started to break, and so they made the announcement. In a way it was really lucky, because all these people knew by then, and I’d never gotten a standing ovation before. It was so nice of both Adam Moss and Janice Min to say something nice about me; you don’t have a lot of time up there. It ended up being as good as a departure could be.

You were born on Halloween. Any traditions?

Well, last year was an anomaly, because in addition to getting fired, which was an amazing emotional experience—everyone should have it—the other emotional experience I had was that my father died earlier in the year, which was way more devastating than I thought. Then my mom had to have her hip replaced, so on my birthday I was with my mom, wife, and siblings. I had dinner with my mom at her house and the next night I went out and celebrated. Usually, we go to our friends’ house, which is like trick-or-treat central. When all our children were little, we’d go there and trick or treat. We had this little red wagon that we’d have tequila, bourbon, and beer in; we would share it with other people who were out watching their kids trick or treat. Now that we’ve aged out of walking around pretending to have [young] children, our friend Molly orders a brisket from Boston, we drink tequila, hand out candy to all the little kids, and it’s nice. These traditions come to an end, but I think we’ll do it this year.

This year, you’ll turn 60, right? According to one of Esquire’s Rules for Men, you don’t start understanding life well until you’re 40. What have you figured out at 60?

If you drink good tequila, and only good tequila all night long, you’ll never get hungover.

Read the issue HERE.