Broadway, TV, and film producer Richie Jackson came of age in New York City during the early years of the AIDS crisis. Through luck and his own relentless vigilance, he managed to avoid the tragic fate that befell so many gay men during that time. He fell in love and had a son with actor BD Wong. He found tremendous professional success in the entertainment industry, working with actors including Harvey Fierstein, John Cameron Mitchell, and Edie Falco. His relationship with Wong ended and he met and married Broadway producer and red carpet fashion provocateur Jordan Roth, and had another son. It’s a life few gay men of his generation got a chance to live, full of highs – marriage, children, and even just living openly – that many in the gay community never even imagined possible. He’s a very fortunate man, and he does not take his good fortune lightly.

When his oldest son, now 19, came out to him, Jackson was thrilled. It was something they could share, something they had in common that, to Jackson, was the very best thing about him. But his son didn’t really see it that way. To him, being gay was no big deal. Growing up affluent in New York City during the Obama years with openly gay parents, he was spared most of the traumas suffered by so many gay people, his father included. Yet it was those experiences that made his father the compassionate, loving, tough, vigilant, and generous person he is (and he really is all those things and more). So Jackson wrote his son a book, Gay Like Me: A Father Writes to His Son, to teach him about what it really means to be gay – the beauty and struggle and love and fear and innate specialness of it.

Gay Like Me is a book written by a gay man to his gay son, but it is not just for gay people. It’s for everyone. For every parent, whether their child is gay or not. For every person who has ever known and cared about a gay man. Even for people who just find themselves wondering, “What’s the big deal with gay people, anyway?” It’s a thoughtful, vulnerable, and intimate account of gay history and a personal gay story that is both singular and universal.

The Daily sat down with Jackson before the holidays to talk about the book, which is available beginning today, and what it means to be gay in America right now.

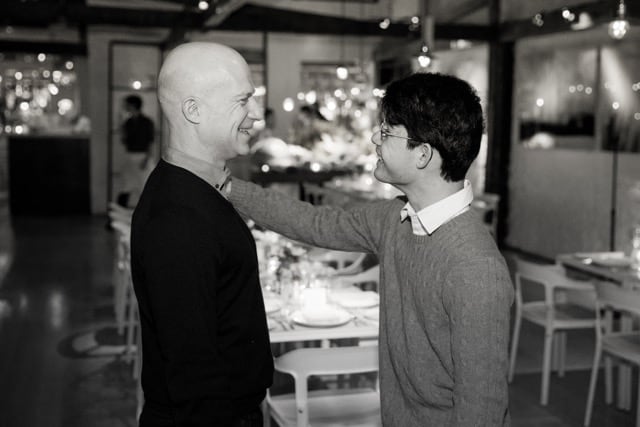

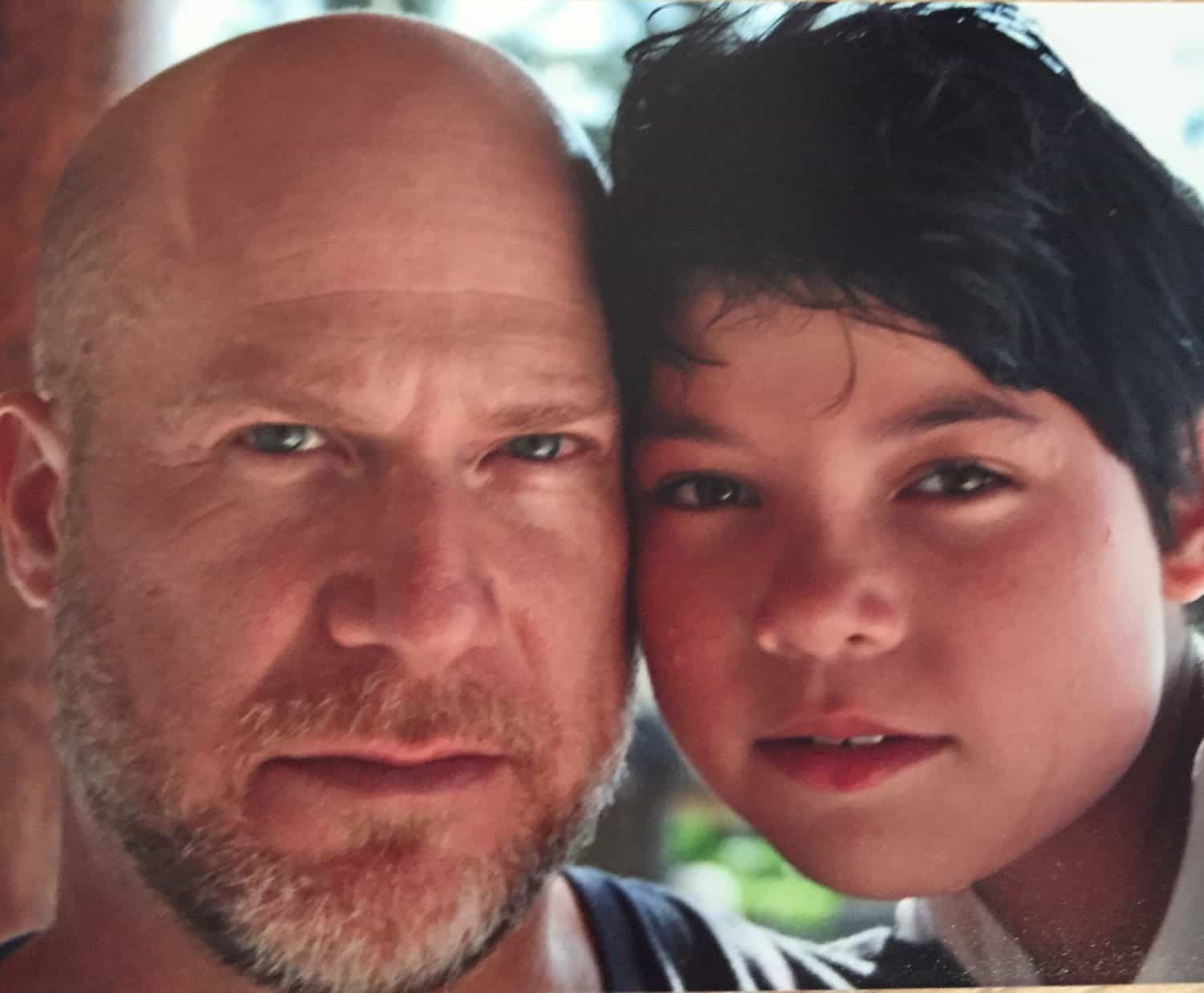

Richie Jackson (right) with his husband, Jordan Roth, and their sons, Levi Roth and Jackson Foo Wong

Congratulations on your book! It’s wonderful. Has your son read it yet?

Not yet. I finished it right as he started college and he’s putting his reading list for school first. The whole point of writing it was to give him this information before he left our house, but as a parent, all you can do is lay the information at their feet. He’ll read it when he’s ready. I asked his permission to write it and he said, “absolutely.”

What was that discussion like?

He’s a very private person and there have been moments in our lives when I’ve had to explain to him that, as a family, we can help other people just by being visible. For instance, when Jordan [Roth] and I were married, The New York Times covered our wedding and wrote this beautiful piece and I said, “There’s going to be a picture of you in The New York Times.” He was 12 years old, but he understood that not everybody could get married and he understood that it was important to have a same-sex wedding in The New York Times, to see a gay couple that had a child, and he said yes.

Years later, I was on an airplane and a flight attendant in his 60’s came up to me and asked if I was married to Jordan Roth. I said “Yes”, he said, “Your wedding story is hanging on my refrigerator. I read it and I thought, ‘They fought for love. I want that.’” And then I was able to go home and say to Jackson, “look what you did.” That was the whole point. So when he was 16 and I said I had the idea for this book, he said yes straight away.

How long after he came out did you start talking to him about writing the book?

When he came out, the first thing he said to me was, “Dad, it’s not a big deal anymore.” I think it’s a really big deal and I wanted to help him understand what a gift it is and that if he diminished it, he would not be taking full advantage of what he’d been given.

Jackson Wong and Richie Jackson

I started thinking about all the things I wanted to tell him: about the creativity, about the blank canvas his life is now, that he can be anything he wants, and about the extraordinary human beings he would meet.

Then Donald Trump was elected and I thought, “Oh, I really have to warn him, now.” Because it was one thing to come out in the world of President Obama, but another to live in a world that elected Donald Trump and Mike Pence. I thought, “I have to tell him. He’s not even aware of how alert you have to constantly be as a gay man. He doesn’t know that I have not let my guard down in 36 years.” I wanted to make sure that when he left our house, I had helped him build a gay guard, becasue he dosen’t understand yet how important that is.

How has he been liking college ?

He likes it. I think he feels wildly over-parented by us, so he was ready to go. As a parent, all you want is for them to make a friend, because you feel like once they connect with someone, they’ll be okay. So now he has a group of friends, and he’s joined the LGBTQ group in the school he’s in. I think he’s doing really well. He’s adjusting to it much better than I’ve adjusted to him being away, that’s for sure!

Richie Jackson and Jackson Wong

How much did you involve him in the writing process? Did you talk to him about what you were writing as you went along? Are there things he’s going to learn in reading the book that he doesn’t already know?

I have written about things no parent wants their child to know about their past: mistakes I’ve made, things I’ve done that I wouldn’t want him to do, my first sexual experiences, which were not positive at all. He’ll make his own mistakes, but it is my hope that he will be able to avoid making the same mistakes I made and, at the same time, understand that you can make mistakes and still survive and thrive, that it’s fine if he makes mistakes and that struggles and challenges are part of life. I don’t want him to just see me as fully formed. I want him to know about the challenges I’ve faced.

He didn’t know how alert we were to the dangers [of being a gay family] when he was younger. How, when we were in parks, I was always clocking who was around us. When he called Jordan “daddy,” I would look around to see if anybody who heard could pose a danger to us. We took his birth certificate on every single trip and when we went on family vacations, we made sure they were to places that were safe for us. When our extended family would say, “Hey, we’re going to do this for Christmas,” we had to check to make sure it was okay for us to go. He wasn’t aware of any of that, so that’s all going to be new information for him as well.

When I started all this, I said to him, “I’m going to write you a book to teach you how to be gay.” and he said, “I know how to be gay, dad.”

What does he think it means to be gay?

He says that it’s not a big deal anymore.

You know, as we gain visibility and representation, and as there are more laws to protect us (for now, at least), people start to say, “Oh, this isn’t a big deal anymore.” And my point to him is that I think [my gayness] is the most important thing about me. It’s the best thing about me. He doesn’t have to put it in the same hierarchy that I have, but I don’t want him to diminish it, either. I want him to know that he has been chosen. Only 4.5% of Americans are LGBTQ. We’re not a defect. We’re not worthless. We’re chosen to see the world from a different point of view. And that’s what I wanted to help him understand – what a gift it is not to be like everybody else.

You write about a lot of very personal things in the book. Was anything off-limits? Where did you draw the line?

When my editor read my first draft, he said “This is very brave.” I asked Jordan if I had written something I shouldn’t have and he said, “No, you’re being vulnerable and in this day and age, that’s rare.”

Richie Jackson and Jordan Roth (Tony Honors)

It’s certainly very vulnerable to write about your first sexual experiences the way that you do.

I wanted to do that because my son is the same age I was when I started to have sex. I feel very damaged by my first sexual experiences, and as he begins to have physical relationships of his own, I want him to be more aware than I was, to know that it can be awkward, that not everybody is going to be comfortable with who they are, and that as much as you might want to be vulnerable with someone, you also need to protect yourself.

I was more worried about my parents reading it than my son or some stranger.

And what did they say?

My mother was texting me as she was read it and she was like, “Oh, this is gut wrenching, I don’t know how you did this. It must have been so hard to relive all this. I’m sorry I wasn’t there for you your first year of college. I had no idea what you were going through.”

It was really a very nice response. She hasn’t asked me about any of the details and I’m perfectly happy with that.

Jackson and his mother, Carol Jackson, dancing at his wedding to Jordan Roth

What about your dad?

My dad is a writer and he told me he thought the writing was fantastic and I had great word choice, but said nothing about the details, and you know what? I’ll take that.

Richie Jackson and his father, Paul Jackson

One of my favorite parts of the book, one that had me laughing out loud in my room when I read it, is when you talk about the first time you had sex with a woman. The only time, I’m assuming.

Yes. It was all planned out. We were at the end of our senior year of high school. We knew where we were going to college and that we were planning on going to prom together and she said, “My mom got me an IUD for college. Let’s try it out!”

We decided to do it before prom to take the pressure off. And she said, “My parents want to meet you, so come over and we’ll have tea with them and then we’ll go upstairs.” So I put on a blazer and I went over to her house and her parents were sitting at the kitchen table and they served us tea and pound cake and we talked about me going to college and what I wanted to do and where she was going to college and then we excused ourselves and went upstairs.

And they knew you were going upstairs to have sex?

Absolutely.

What year was this?

1983.

That’s very progressive. Your parents seem pretty progressive too, though.

Honestly, my parents were not very open about sex. The only thing my mother ever said to me about sex was, “You know it’s okay to masturbate, right?”

But this family was very different and I remember thinking,”Oh, wow, what a difference a gender makes! I had been sneaking around with boys for several years at that point, always in basements or behind bushes in parks, in my car in an abandoned parking lot, and here I was in a bed with her parents just downstairs and I thought, “Is this what straight kids get?”

And did this friend of yours know that you were gay?

No, I didn’t talk about that.

Did you talk to her after high school?

Yeah, we talked during college a lot and I’m still in touch with her now.

It’s obvious that experience with your friend was quite formative for you, because you write in your book about facilitating the same kind of experience for your son when he was ready to have sex for the first time. What was it like being on the other side of that scenario?

That was part of why I felt the urgent need to write this book for him. Because when he was 15 and kissing his first boy, his therapist, who we had been seeing for many years, said during one of our parent check-ins, said she was going to give us the same advice she gave to the parents of straight kids, which was not to let him be with a boy behind closed doors in his bedroom.

And I said, “It’s not the same with a straight kid. My son cannot go sit on a park bench and kiss a boy. They will be harassed, or beaten up, or worse. The safest place is in my home, in his bedroom, with the door closed.” I was alarmed that had not occurred to her.

That’s part of why this book is so important. Straight people don’t know how we have to protect ourselves, how vigilant we have to be every day. It starts when you are 15 and you are kissing a boy for the first time. You have to know that you can’t do it just anywhere.

So he would come home with a boy and then, when the boy left, we would talk about what happened, was he comfortable, just have a really good conversation. It was very different from the times I was in a basement or hiding behind the very last bush of the end of the park and then would go home and never tell anybody. He got to walk out of his bedroom and know that I supported what he had just done and we were able to talk about it.

Jackson Foo Wong and Richie Jackson

What did the therapist say when you told her that her advice was wrong?

I don’t remember specifically, but I was not satisfied with her response and I’m still upset about it. My son says I need to get over it.

Do you feel like it is your responsibility to educate non-queer people about queer identity and queer politics?

I feel very strongly that if people who aren’t gay were able to read Gay Like Me, they would better understand what it is to be an LGBTQ person.

At the same time, I want young LGBTQ people to see that there is a life waiting for them that is full of love and potential and exuberance, and that they are worthy.

Every time my family and I talk, or go somewhere, or have our pictures taken, or post on social media, it is to show those young people, and maybe their families, that we are living lives full of love. And it’s not in spite of being gay, but because of it. The extraordinary Jordan Roth would not love me if I scrubbed off my gayness in any part of my life.

Richie Jackson and Jordan Roth

That’s lovely. And it is hard to find. There is so much self-loathing and shame within the gay community. And it can be hard to love someone else when you hate yourself.

I think someone else can help you to love yourself, though. Something Jordan and I figured out is that we don’t have a general way of loving each other. We love each other the way each of us needs to be loved and when that happens, you begin to heal from your traumas. He loves me the way he knows I want to be loved. And when I met him, I understood immediately what he needed for me: he needed to be seen, to be listened to. I think the mistake people make when they start dating someone is that they let themselves be led by this vague idea they have of what love is and how to be in a relationship. You need to tailor how you love based on who you’re falling in love with.

Towards the end of the book, you talk about the danger of passing for straight and I agree. I think the obsession with “passing” and the way our community so often fetishizes straightness is incredibly toxic. The people who do pass have a false sense of security and, in my experience, often hold themselves apart from those who don’t. As if they are somehow superior because some random person on the street thinks they’re straight.

In my life, I always talk about being gay, or, now that i’m married, I make sure to mention my husband. I don’t want anybody to think I’m straight. I don’t want to be straight. I’ve never wanted to be straight. I don’t envy people who are straight. I want people to see me from what I am and so I make sure people know that I’m gay. I do not want to pass.

Jordan Roth, Richie Jackson, and Jackson Wong at the birth of Levi Roth

That’s wonderful. It’s very difficult for me to see white, financially secure, gay men hiding in the closet. You say in your book that everyone comes out in their own time, that they each have their own story and their own journey, but I get very angry when I see the most privileged among us hiding. Especially when they are gay in private, getting off with other gay men, but too cowardly to actually live out in the open.

If someone is simply being gay to get off, then they’re suffering. If they haven’t made being gay part of their entire life, then I feel sad for them because they are not taking full advantage of their gayness.

I don’t want to judge why someone is in the closet. They might have a family member they are afraid of. There are a lot of reasons someone might be in the closet. And I understand your anger at people who take advantage of all of the privileges that come with being a white male in this society and hide the one part of them that might make things a little harder for them, but I also have compassion for them because they’re the ones who are missing out. They don’t have what you and I have. Their lives are not authentic.

It’s more than that, though. I mean, you talk about this in the book, how important it is to be visible, to show people that we exist, even if they don’t want to believe it, and to show people who are like us that they are not alone. But these men, hiding in plain sight, are not just hurting themselves. They are hurting all of us. And the damage that they are doing by pretending to be straight simply for the preservation of their own egos and privilege is much greater, I think, than any imagined harm they would face were they to actually come out.

I understand what you mean, I do, but I think people who aren’t ready to be out, we might find that 10 years from now, those people have a different point of view. Sadly, I think that we are giving short shrift to gay people who are in the closet. We’re celebrating children like mine who come out at 15. We’re celebrating these extraordinary kids who stand up in auditoriums and tell their schools that they’re trans or gay or gender fluid, but a gay person who lives in the closet for most of their life, has as legitimate a gay experience as my 15 year old son who has already come out.

You’re right. That is a legitimate gay experience. And certainly there are many parts of this country where the closet is a necessity. There is safety in the closet. But not everyone can hide. For many of us, our closets are made of glass. We have no choice but to be out. And that can leave us very vulnerable and angry at those who are better equipped than us to deal with the realities of being gay in this country, but choose to remain hidden. At the same time, I do see what you’re saying. It is certainly more empowering and freeing for me personally to look on these people with compassion rather than anger. I just struggle with how to make that shift in perspective.

Try not to look at people who are in the closet as being purposely harmful to us. That’s mind reading – looking at the outside and thinking you know what’s going on inside. We don’t know what everybody’s journey is and, for me, I feel for the person who is not getting out of their gayness what I get out of mine. I’m happy and my happiness comes from being gay. It’s not like I’m happy and, oh yeah, I’m gay too. All of my happiness stems from being gay. So I really feel for people who close themselves off to that.

Is it ever hard to be an out gay man working in entertainment? You’re a producer and I feel like there is this awful tension around sexuality in entertainment. People think of the entertainment industry as being very open and gay-positive, but in many ways I have found it to be deeply homophobic and full of self-loathing.

I’ve had good luck. A bit of it is just where I’ve gravitated in my work, working with Harvey Fierstein and John Cameron Mitchell – these important gay voices in our culture. I think the tension now is about how to sell – whether it is possible to sell a gay actor as the star of a movie – and my feeling lately has been that gay actors have to play gay parts. It’s just unacceptable to keep casting straight actors to play gay.

I was recently asked to come on board a film based on a gay novel and when I asked who they were thinking of casting, the list was all straight stars. They said they needed a star to get the movie made and I said, “I can’t [work on this].” And they said, “Would you rather a movie about a gay person not be made?” and I said. “Yes.”

Harvey Fierstein and Richie Jackson

Why?

For a lot of reasons. One is that gay actors are shut out of playing straight all the time and, just for employment purposes, they cannot also be shut out from playing gay. Also, we should tell our own stories; we should portray ourselves and make sure we’re telling our stories correctly. And the most important reason for me is that I had the experience, as a 17-year-old closeted gay kid, of seeing Harvey Fierstein on Broadway in Torch Song Trilogy. That was the first gay character I ever came in contact with and then I had the opportunity to follow him off stage, to read everything he said in the paper, and it was extraordinary to learn about how to be gay from this actor who I had just seen on Broadway. If we’re casting straight actors play gay or non-trans actors to play trans, our LGBTQ youth are not getting the role models they need off stage and off screen. And that, I think, is really dangerous.

Of course, people who benefit from this situation, or prefer not to think about it, love to argue that a good actor should be able to portray any character.

Yeah, but that’s a capricious argument because they don’t let gay people play straight.

Exactly. It also shows that those people don’t actually understand what acting is all about. Acting is about truth and honesty. And being gay is not just some, to use a common acting term, “imaginary circumstance.” As a gay man, I can tell you that it permeates every moment of my life, every interaction, every feeling. It’s a much deeper experience than those people realize or want to accept.

It is the filter through which we see and think about everything. And that cannot be acted. How many straight actors have you seen where their simple way of playing gay is having a limp wrist? That’s their affectation.

Jordan and I went to see a gay movie that was entirley acted by straight actors and it was heartbreaking. They didn’t have the soul or spirit of the gay experience in any of them so the movie lacked authenticity. The very next morning I sent Jordan the Langston Hughes poem “Notes on Commercial Theatre” because it talks about how we have to tell our own stories, not let people steal our stories and portray us. Because they’ll change it. They’ll bend it to their own ideas.

You also talk in the book about the difficulty of having people in your family who support Trump. Jordan’s father, Steven Roth, was even Trump’s economic adviser during his 2016 presidential campaign.

He still supports him. It’s very painful. It’s a betrayal. You cannot be a Trump ally and a LGBTQ ally. It’s impossible. If you support Donald Trump, you’re endangering the lives of gay people and the only way that I reconcile it is that they just don’t understand what it takes to be gay, what it means, and that it’s not just a part of us. They don’t appreciate all of what it means to be gay and they don’t appreciate the vigilence it takes to be gay in this country and so it’s as generous point of view I can possibly have.

You must still spend time with him, though. How do you stand it?

It’s not just the Trump thing. Jordan and I were told by a different family member at a family event once that he didn’t think a baker should be forced to make a cake for a gay couple. We were literally told at our own family dinner that a member of our family doesn’t think we deserve the same rights he has.

I talk about this in the book, that as a gay person, you need two distinct lines of vision every day. You need to have a realistic view of how the country sees you and be very vigilant and clear about it and then you need to keep a separate and protected beautiful view of your gay self that you do not let anybody soil. The sad thing is Jordan and I need that double vision at our own family table when we’re at Thanksgiving. And we’re not unique in that. A lot of gay people have that and it’s painful and as I said, the only possible way that I can continue to participate in family events is to think that they just don’t get it. Now, maybe after they read my book they’ll see how much it means to us to be gay, how important and useful to us it is to be gay, and also what it takes to be gay every single day, and maybe they’ll change.

And if they don’t ?

It’s very hard to ask your spouse not to speak to their parents. You just can’t do it.

I was speaking to an actor after the election, who told me how difficult it was to go home for Christmas that year because his family voted from Trump. And then a bunch of other actors and friends of mine told me the same story and I called up a writer and said “I have an idea for a benefit for Broadway Cares. We should get all these people to write monologues about what it was like for a gay person to go back home for Thanksgiving after Trump was elected.”

That sounds truly painful. I honestly don’t know why or how people put themselves through that.

One of the things I love about your book is that it is written from one gay person to another. It’s intimate, because you are writing to your son, but it is also public, because it is a published book, which means straight people can read it and learn from it, if they’ll just take the initiative to pick it up. I think a lot of straight people are quite lazy about this stuff. They know and like a few gay people and they think that means they know what it’s like to be gay and to really be an ally. Or they ask us questions as if it was our responsibility to take time out of our lives to educate them, when there are resources all around them, like this book, if they would only put in a tiny bit of effort to educate themselves.

You know, the only thing straight people ever want to ask is, “Were you born gay, or is it a choice?” That’s as deep as their curiosity goes.

And as you say in the book, it’s because all they really want is to be absolved of responsibility, especially in the cases of straight parents with gay kids. Even if they say they’re allies, so often they want this absolution because on some level they see being gay as a negative.

And we all know straight people who think they’re better than us because they’re straight. And not just men. I’ve experienced this with a lot of women too.

Me too, which is why I’m so excited that this book exists. Because more and more, I find myself in situations where I’m having to wade through these awful discussions with friends of mine who have become parents and start talking about the possibility of their children being gay as if it were some horror looming on the horizon. I don’t think they realize how hurtful that is to me or how much that attitude will color how their children see gayness, whether they turn out to be gay themselves or not. And I honestly just don’t have the energy to get into it with them when it comes up. But now I don’t have to! I can give them this book and say, “Read this. And if you still have questions, read it again. And if you still have questions after that, then we can talk.”

I find it so interesting when parents say it doesn’t matter to them [if their child is gay]. I’m like, your child is going to tell you this huge thing and your response is going to be “it doesn’t matter?” There are better responses and I think every parent who thinks they have a gay child can either be that child’s first trauma – their first obstacle to overcome – or they can choose to help educate their young gay child and help raise them with gay self-esteem. And it lays out in my book how you do that – through history, though art, through words. The culture of gayness helps you claim your space. But the other thing these parents get to do is say, “Instead of being the obstacle, I’m going to get on this magical ride [with my child]. I’m going to have a relationship with my gay child and they’re going to have a life that I never expected and it will be more interesting and more varied than I imagined when I was thinking what my child’s life will be. I just think to myself, “Straight parents, get on the ride! Because it will take you to places you’ve never even imagined.”

Richie Jackson and Jackson Wong

Gay Like Me: A Father Writes to His Son, by Richie Jackson, is available now from Harper Collins Publishers.

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Instagram to stay up to date on all the latest fashion news and juicy industry gossip.