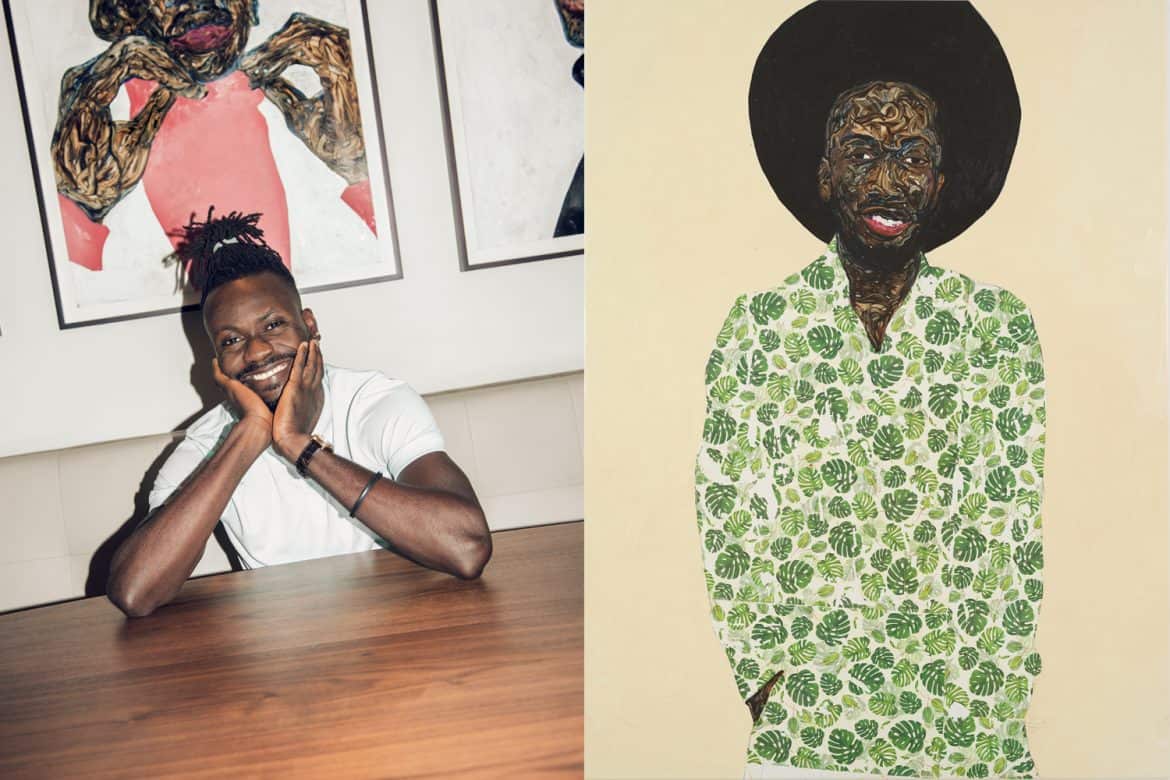

Amoako Boafo is about to blow up. Born in Ghana, Boafo lives and works in Vienna, Austria, and is making his Art Basel Miami debut with Chicago’s Mariane Ibrahim Gallery. Ahead, Boafo opens up about his fascinating background, creative process, and career trajectory.

What was your childhood like in Accra, Ghana?

I have two siblings, but my father died [when I was young], so I was raised by my mom and my grandma. After high school I went to art college, which was not something anyone wanted me to do. If you’re born and raised in Ghana, your parents don’t want you to be an artist because, in Ghana, it doesn’t really pay off. They like art and painting, but they don’t believe anyone will really invest money in it, so it wasn’t something anyone dreamed of me doing. But, of course, I wanted to be an artist — it makes me free — so I just did it.

What did your mother and grandmother say when you told them?

Art was really an escape for me, a way for me to be alone with myself. When I told my mom I wanted to study art, she said, “You know that’s not going to bring you any money, right?” I was like, “Yeah, I know.” And she said, “And you’ll still have to get a job afterward.” I said, “Yeah, I know.”

Where did your interest in art come from?

Art is not anything I could be around. I didn’t see it anywhere. I was more self-taught. Growing up, my friends and I would have art competitions. We would take a cartoon or something, and we would all draw the same thing and see who did it best. That was really how I started.

Did you win a lot of those contests?

Well… I would say yes. [Laughs] But not all the time. You have to admire when someone else does better than you. And that’s how you learn from each other.

What was your arts education like?

First, I went to art school in Ghana. I knew I wanted to learn how to paint, and it didn’t really matter where. I knew a few people who had been to art school already, so I was like, “Can I see what you did in school?” Then, I would compare my work to what they showed me, and see who I wanted to paint like. I was considering two schools, but I was blown away by the technique of a guy I knew who went to Ghanatta College of Arts and Design.

What was college like?

I arrived a bit late — maybe a month or so — and they had all advanced in shading, still life, all these things. I remember the whole class was making fun of someone; they put their drawing on the board for everyone to see, and I saw the drawing and I was like, “This is amazing! How can I get myself to do that?” But they were making fun of it! It turned out the person wasn’t good enough, and I was like, “Oh, s**t!” Everything I had been proud of showing, I decided I had to hide. So I hid everything and started looking around the class, seeing which students were better and making friends with the ones who were willing to help other students [like me].

Your professors couldn’t help you?

Your professor comes every day to tell you what you have to do, but it’s a class of 47 people, so he doesn’t have time to talk with every student. He does whatever he does on the board and then you just have to figure it out. Some students who are really good, who get it, you have to become good friends with them. So that’s what I did. I actually learned from my colleagues because they were good enough to understand what the teacher was teaching, and then they could teach me.

How did you end up in Vienna?

After Ghanatta, I met someone in Ghana who was from Vienna, and encouraged me to go there. I didn’t have any intention of going there to study because I already knew how to paint, but it was something new, in a new space. The education you get there is good and you pay almost nothing, so I applied to the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and I got in.

What was it like going to Vienna for the first time?

Well, when I arrived, it was winter, and it was my first winter in the snow.

What did you think of your inaugural encounter with truly chilly weather?

For me, it was just cold. I didn’t get it. Also, the streets were empty. I was like, “Where is everyone?” I had seen Europe on TV, but everyone was outside — I didn’t get that people are only outside during the summertime, and during winter everyone is indoors. I didn’t like it.

But you stuck it out, and still live there.

Well, I have my wife; plus, the university [is there]. I did manage to actually make good friends, who helped me navigate the art scene, because being black, it was quite hard to get anywhere. But now Vienna is a second home. Although Ghana is always home.

Your own nonprofit arts organization, We Dey, is in Vienna, too.

From the beginning, everywhere I applied to show, they said they didn’t show anything African. To be an artist, to create and not have a place to show, is a great frustration. It makes you feel like you’re not good enough. So I talked to my wife [about creating a space for artists like me], and we applied for a grant from the city.

The first time we applied, we got nothing, but the second time, we got a grant for the year. To have a physical space, you need money, and I wasn’t selling many paintings back then, so it was hard. But we managed to get the space together, and did the first open call, for POC artists of any discipline — performance, drawing, painting. It was good. It was difficult to maintain the space, but we do yearly crowdfunding, and now things are getting better. I’m also working to have another space in Ghana.

Has Vienna’s arts community changed its attitudes toward your race and Ghanese heritage as your success has grown?

After my breakthrough, a few galleries in Vienna actually wanted to show me. But that’s just them wanting to make money off of me, because anyone who has my painting will be able to sell it. At this point, I’m not really interested in that — I’m interested in having museum shows, and having my works in places that will actually help my career, not just selling to anyone who has money.

Your work is reminiscent of another famous Austrian artist, Egon Schiele. Is that intentional?

When I arrived in Vienna, I didn’t think of changing the way I paint or anything, but I heard certain names over and over — Klimt, Schiele, Lassnig — and I wanted to see why they were so famous. I actually love their paintings, and every now and then I would [test myself] to see if I could paint the way they were painting. I could, of course. But with Schiele, I was most interested in seeing how he got his results. You could really see all the brushstrokes and colors he mixed to make a painting, unlike Klimt, [whose work is] very well mixed, realistic, and decorated, which is also good. I just want my paintings to be as free as possible, and Schiele gave me that vibe — the strokes, characters, and composition.

Do you use your fingers to create such a loose, free aesthetic?

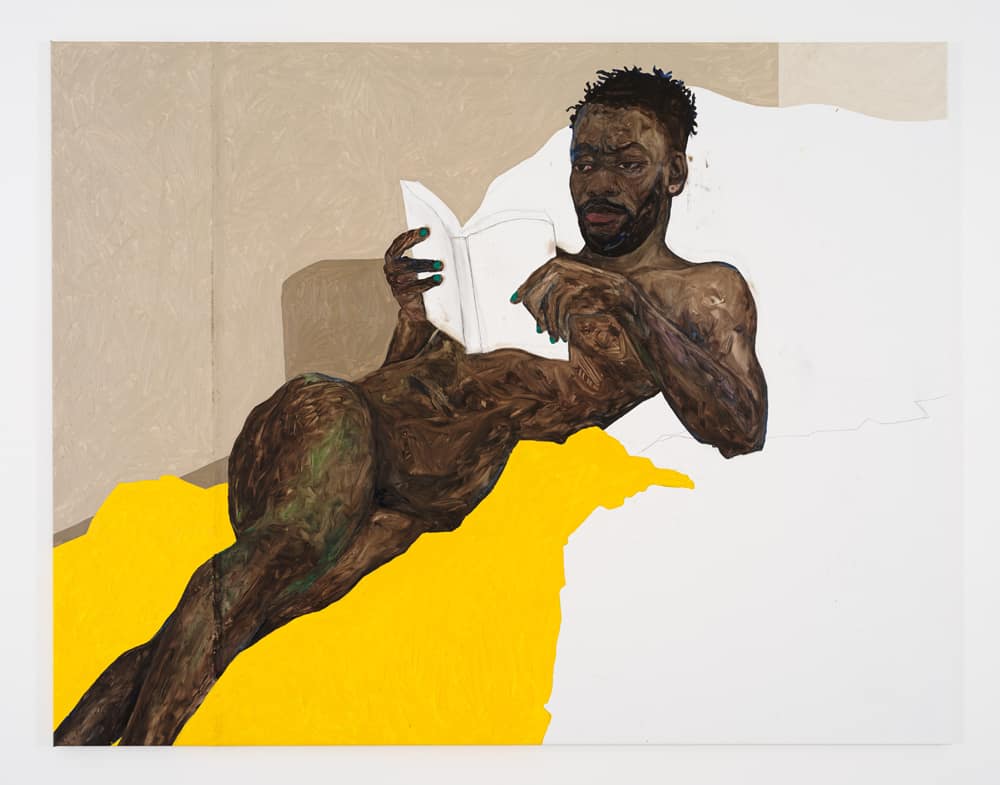

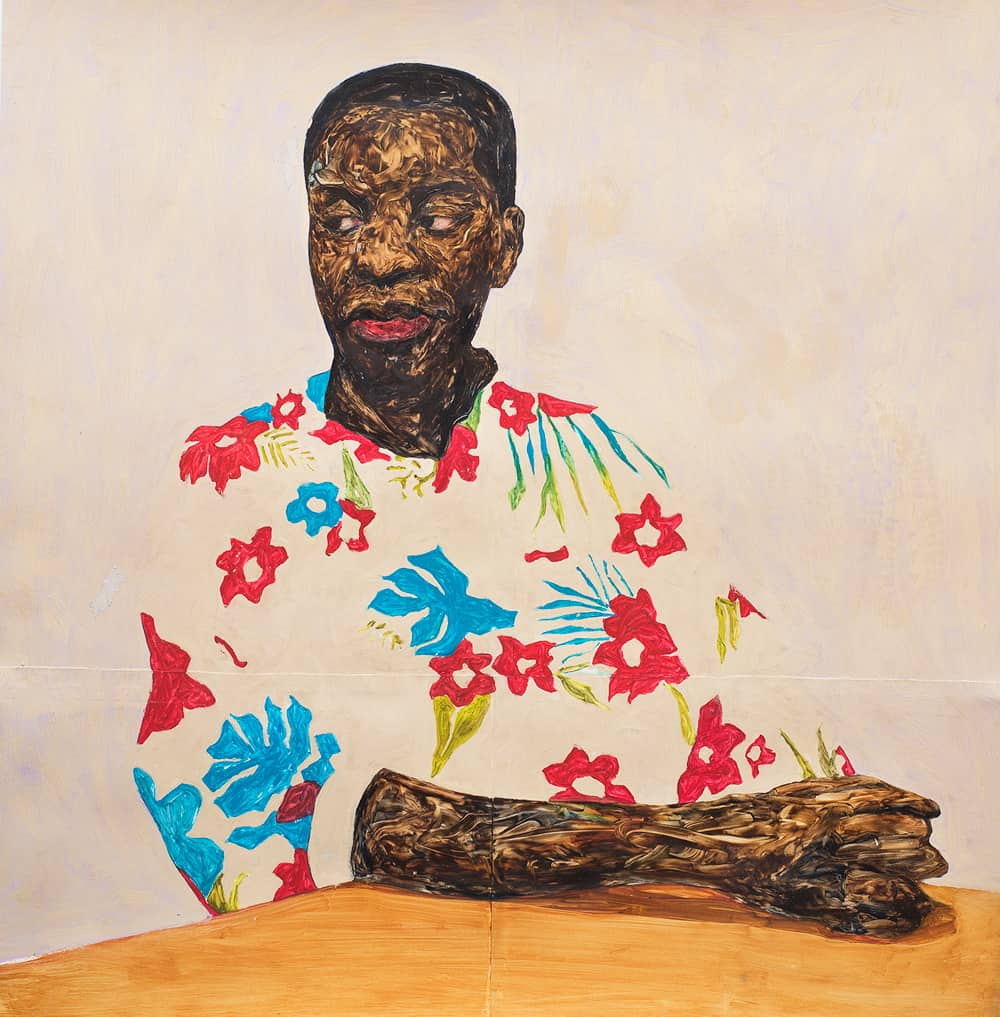

Yeah. I tried a few techniques, like with a brush, but I feel much more free when I’m painting with my fingers; I like the fact that I don’t have so much control.

Do you remember the first Schiele painting you ever saw?

It was a self-portrait with a flower or a plant beside him. When I arrived at the university, a few people said, “You’re good, but if you want to sell, you have to change the characters you paint.” Meaning I would have to paint white people. For a moment, I was like, “Okay.” But then I was like, “No. I’m painting myself, and it’s important that I paint myself. I don’t see why I, as a black person, am not good enough to be shown in a gallery.” Then I saw Schiele’s self-portrait, and it actually confirmed for me that I should keep painting what I was painting. It helped to see another artist just dealing with himself and the people around him.

How do you choose your subjects?

I like [facial] expressions. I choose images based on how I feel, and I choose characters based on what they’re doing in society. I am all about space — people who create space for others — and I choose characters who are doing something for the community.

Do you do much preparatory work?

I paint a lot in my head. But I don’t do a lot of work before I start painting, because it takes a long time and there’s a lot of disappointment if you don’t get it the way you planned.

When did you first start to feel like you’d really made it as an artist?

Probably when Kehinde Wiley bought one of my paintings. I think he was actually the one that sort of made all of this [success] happen. When he bought that painting, I was nowhere. I mean, I was doing okay, but no one really knew me. Then he bought the painting and introduced me to his gallery, and that’s when everything started. The first time he wrote to me I was like, “Oh, s**t! This is good.” I didn’t think I had “made it,” but I got a certain satisfaction from that. It made me feel like I was doing something good.

What’s the most recent work of art that really blew you away?

A piece by El Anatsui in the Ghana pavilion at the Venice Biennale. He’s a sculptor who uses bottle caps for his work, and does really huge pieces. I’d only ever seen images, but when you see the real piece [in person], you sort of lose yourself in it.

Your paintings are often quite large, too — up to eight square feet. Why do like working in larger scales?

When I got to Vienna, I had the feeling that no one really saw me, as a black person, so I wanted to create something you wouldn’t be able to ignore, something that was in your face. So I decided to go big.

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Instagram to stay up to date on all the latest fashion news and juicy industry gossip.